Were there Black Suffragettes in Britain?

4-5 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | October 6, 2020

Sarah Parker Remond is one of the only Black women that we can be sure supported the British suffrage movement. Who was she and where were the other Black suffragettes? Sophie Goode takes a closer look.

It has been over 100 years since the Suffragettes secured the vote for women in Britain and you would be hard-pressed to find someone who didn’t now know the names Emmeline Pankhurst, Millicent Fawcett or Emily Davison. However, ask these same people to name a Black suffragette and it is highly unlikely you would receive an answer.

We know that Britain was already a multicultural country by the 1900s with a substantial population of African and West Indian immigrants, so why is it that we know so little about Black British women at the time and their involvement with the suffrage movement? Were there really no Black Suffragettes or have they been intentionally left out of the story?

Invisible Black British women

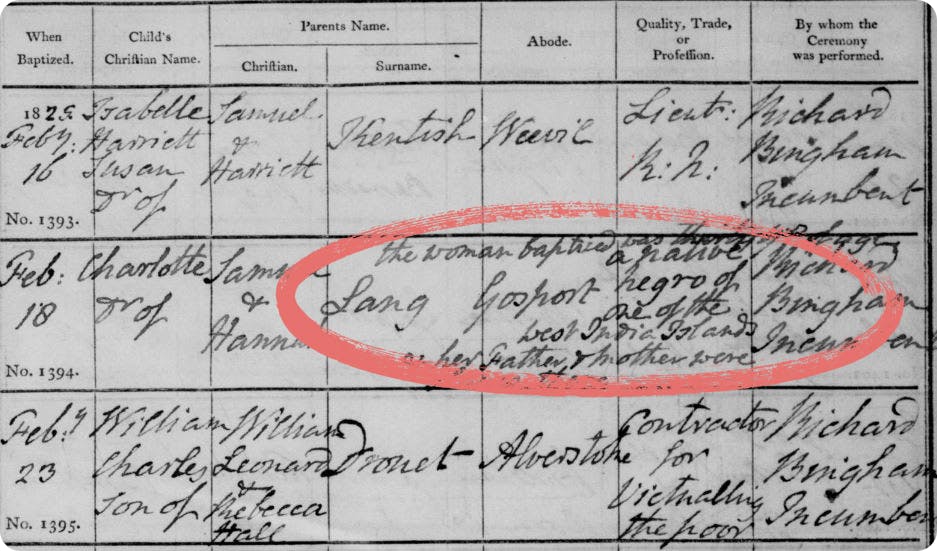

It's been estimated that the black population in Britain in the early 20th century was around 20,000 people, with women making up a small proportion of this demographic. Although the number is probably somewhere around 5,000, we will likely never be able to find out the exact figure. The main reason is that a person's skin colour is often not included in historical records. It wasn’t until the 1991 census that ethnicity was asked, so for records preceding this we can only rely on any additional notes or inferences from a person’s place of birth.

This 1825 baptism register includes the note "The woman baptised was a native negro of the West India Islands & her father and mother were slaves there". View the full record.

It's possible that a large number of black women signed petitions in support of women’s suffrage but that the records we have of them make no reference to their blackness and so their part in the movement will remain invisible.

Sarah Parker Remond

We do have one concrete example of a black woman supporting the British suffrage movement, and that is a signature on the 1866 petition. The petition was signed by around 1,500 women but we don’t know how many of these were Black women, apart from the signature of Sarah Parker Remond. Remond was an African-American abolitionist and suffragist who had come to Britain almost 10 years earlier to lecture on the atrocities that her black brothers and sisters were experiencing back in America at the hands of white people.

In 1858, before her journey to the UK she wrote;

" “I do not fear the wind nor the waves, but I know that, no matter how I go, the spirit of prejudice will meet me.”"

Remond was worried about the reception she would receive in Britain as a black woman but was pleasantly surprised stating that;

"“I have been received here as a sister by white women for the first time in my life.”"

Remond showed a devotion to tackling both racial and gender issues throughout her life, attending the first UK college offering higher education to women and helping end segregated seating at her local theatre.

She died in 1894, aged 70, having witnessed the abolition of slavery but not the suffrage of women, but her part in the beginning of the movement will forever be documented.

Were the suffragettes racist?

Sarah Parker Remond’s concern over treatment due to her skin colour is wholly unsurprising. It is now a widely-accepted fact that the Suffragette movement in the USA was shaded by racism and white supremacy. When women in America did finally get the vote in 1920, the reality was that this achievement primarily benefitted white women and not the black women who also fought for the right. Instead, these women, who had been frequently shunned by the white suffragettes, endured the same intimidation and terrorisation that the men in their family also had to go through when attempting to vote.

Although the British movement wasn’t as explicitly discriminatory as their US counterparts, there was, as there remains to be, racism in the ranks of society. The suffragist movement was at its height at the same time that the British Empire was at its peak, and imperialist views often infiltrated its ranks.

In 1911, a group of Indian women were invited to march in a suffrage procession. Far from being an inclusive event, the procession was intended to demonstrate the sheer size of the Empire and the need for British women to have a vote in order to ‘help’ the women of the various overseas colonies. Of course, no mention was made of these women having the vote themselves.

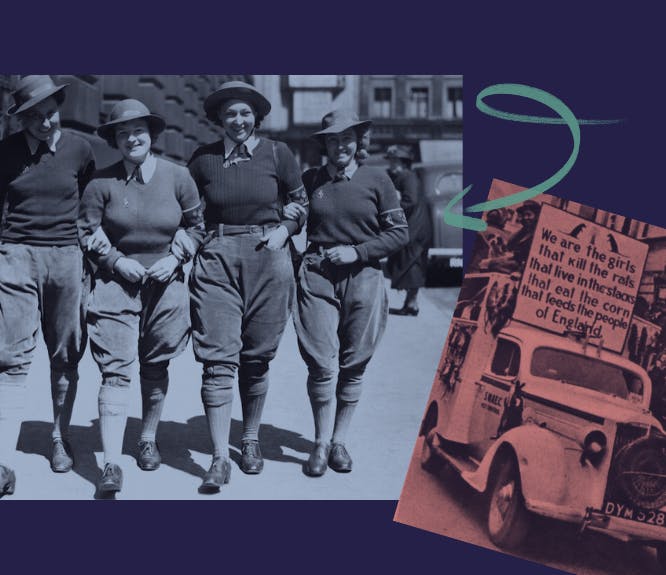

A photo from the 1911 procession where Indian ladies paraded with white suffragettes.

There was even expressed disdain that some WOC in the Empire, Maori women, gained the vote before they did. Hearing stories of the treatment of Black US suffragettes and seeing the white British attitudes towards other women of colour, it is little wonder that Black women were not openly and eagerly involved in the movement.

Domestic duties

The myth of suffragettes as exclusively middle-class women has recently been disputed by historians who propose that the movement was also made up of and supported by a number of working-class women. Women of practically every profession from factory workers to teachers made up the ranks of the movement intending to win the vote, but one profession is notably missing from the marketing and images of the time.

Domestic workers, though making up the majority of women’s work in Britain are absent from public events. Why was this? Firstly, they often worked long, unsociable hours making it difficult, if not impossible, to attend any suffragette events. Secondly, domestic workers had to rely on the service of their employers who may not have all been understanding to ‘The Cause’. Those who were, may not have supported the militant action of the Suffragettes. Going against your employers was not worth the risk of unemployment. While middle-class women were free of time and responsibility, able to put on marches and attend meetings, the working-class domestic servants had to give their support from the sidelines.

Working-class suffragettes. Credit: © Paul Isolani-Smyth/British Library.

But what does all this have to do with Black Suffragettes? While a few black men and women managed to climb the ranks to make a name for themselves, the majority were working-class and most often, servants to the rich.

Searching through census records, it is easy to find an overlap between the women with West Indies as their ‘place of birth’ and ‘domestic servant’ or ‘nurse’ as their occupation.

Black women may not have been out on the streets campaigning or parading. Instead, they were likely serving the white, middle-class families and performing the household duties that allowed women like Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett the time and opportunity to fight for the rights of all women to vote.

Related articles recommended for you

The inspirational work of the Women's Land Army, as told through the Findmypast Photo Collection

History Hub

Seven surprising finds in the 1911 Census

Discoveries

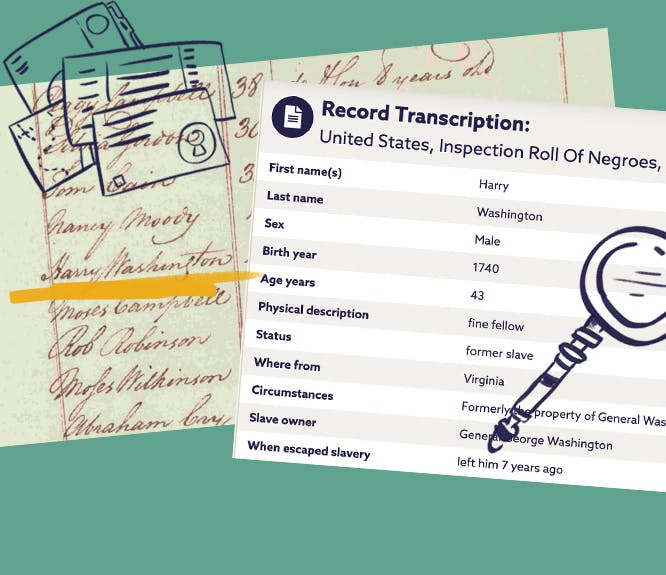

The Black Loyalists and the importance of preserving Black genealogy records

Family Records