How Black Loyalists helped to shape British, American and African history

3-4 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | October 21, 2020

During the American Revolution, the British Army was backed by thousands of Black Loyalists. Here, Jen Baldwin highlights their history in the war and beyond.

After years of tension between Britain and the American Colonies, war broke out on 19 April 1775. At the time, there was a growing belief that King George III would support emancipation and several cases were fought in English courts for the emancipation of escaped American slaves residing in England.

For slaves in America, reaching England meant freedom. Colonial slaveholders feared revolts inspired by these aspirations.

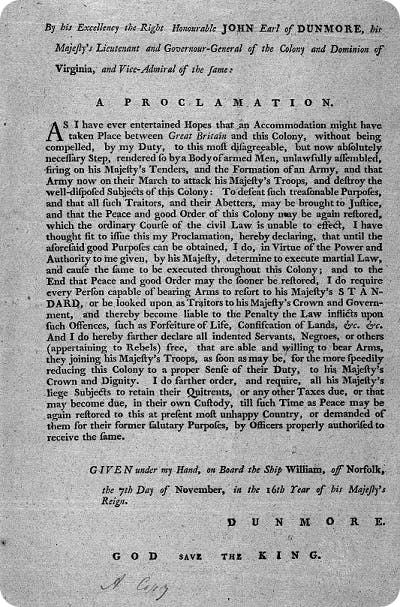

In November 1775, Lord Dunmore issued a heated and controversial Proclamation during his term as Virginia’s royal governor.

The 1775 Proclamation by Virginia Governor, John Earl of Dunmore, declaring martial law. View in full at the Library of Congress.

Calling on all 'able-bodied men' to defend the colony, he included slaves belonging to Patriots. He promised these enslaved recruits' freedom in exchange for service in the British Army.

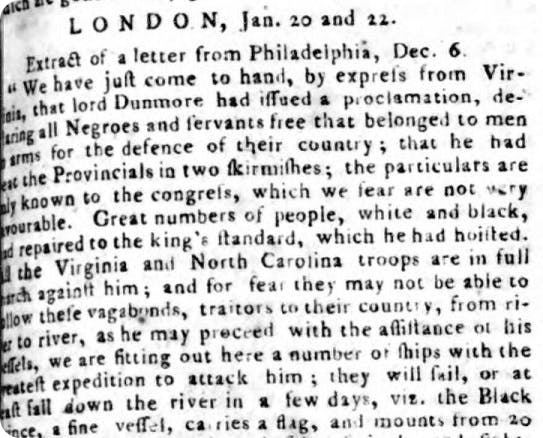

Saunders's News-Letter, 29 January 1776. Read the full article.

It didn’t take long. Within the next 30 days, approximately 800 former slaves fled to Norfolk to enlist. Outraged at the loss of their property, slave owners declared that any runaways would be executed and contradicted the promises made by the British Army. Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation became the first mass emancipation of African slaves in America.

Black Loyalists in the American Revolution

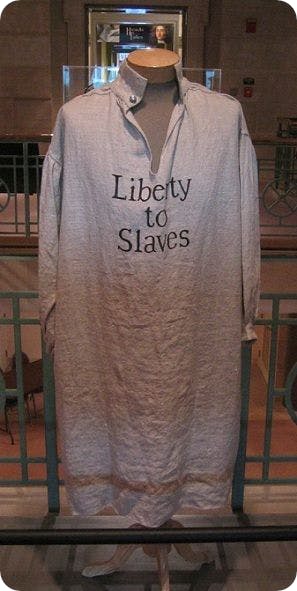

After war broke out, a number of generals issued similar proclamations calling for Loyalists to free their slaves so they could join the ranks of those fighting. A number of units were formed, including the Ethiopian Regiment, Clinton’s Black Company of Pioneers and the Jamaica Rangers. In the end, thousands of enslaved people escaped during the war and ran for the British lines seeking their freedom.

A smock worn by the Ethiopian Regiment with 'Liberty to Slaves' emblazoned across the front, on display at The Virginia Historical Society Museum. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The end of the war certainly did not end the conflict, or the debate, around these individuals. Loyalists remaining in the new United States of America wanted the soldiers returned, as reparation for property damage. In many cases, British military leaders wanted to uphold their promises of freedom despite the underlying issues. General George Washington was ordered to retrieve “any American property, including slaves,” from the British via the Treaty of Paris, which was signed in 1783.

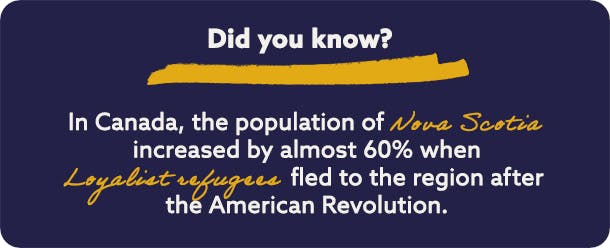

Black Loyalists in Canada

Ultimately, more than 3,000 Black Loyalists were transported to Nova Scotia as part of a compromise that would compensate slave owners and provide certificates of freedom to any person who could prove his service or status. These individuals were recorded in the Book of Negroes by General Carleton. The territory was a difficult one and the climate was harsh.

Many of these individuals had come from the now southern states and the change in their environment was a difficult one to adapt to. They also suffered a great deal of discrimination from the other settlers – many of them slaveholders. This tension led to the first recorded racial riots in Canada, the Shelburne Riots.

Black Loyalists in Sierra Leone

Within just a few years, Black Loyalists were offered the chance to resettle once again in a new colony in Sierra Leone. Nearly 1,200, around half, departed Canada and became part of a new community, Freetown, on the southwest coast of Africa. It remains the capital of Sierra Leone today and is the oldest to be founded by African Americans. The story of Sierra Leone is yet another part of the legacy of the Black Loyalist population and was discussed consistently in newspapers during its establishment and subsequent years.

Chester Courant, 7 February 1792. Read the full article.

1793 saw another movement, during which an additional 3,000 free Blacks were transported to Florida, Nova Scotia and England. When Britain eventually ceded Florida to Spain, these individuals – and many others like them across the south – were seen as 'easy targets' and spoils of war. Many were left behind as Britain pulled out of Florida. The Spanish offered them freedom and the right to bear arms upon conversion to Catholicism and slaves were openly encouraged to escape to the territory.

The full story of Black Loyalists should be recounted in detail, as the nuances and order of chronological events are an important part of the history of this period in America. Use the Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People site created by Canada’s Digital Collection and the Black Loyalist Heritage Center to gain a more thorough understanding and to see transcriptions of the associated documents.

For even more context, read the multi-page History of 1776 published in The Scots Magazine, as the editors outlined the major events of the preceding year in the Colonies. The reports on Virginia start on page 9.

The Scots Magazine, 1 November 1777. Read the full article.

There are so many unknown strands of Black history still to be discovered by most of us today. Do you know if there were Black British suffragettes? Or the full story of the Windrush generation? Only by learning from the mistakes and injustices of the past, can we create a better future together.

Related articles recommended for you

Who Do You Think You Are? Series 21: here's what you missed

Discoveries

Kamala Harris' family tree tells a tale of migration and education

Discoveries

The painstaking process of preserving old family records

Family Records