Surname origins reveal a complex history of slavery in The Bahamas

4-5 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | February 1, 2021

Some Bahamian surnames come from freed slaves adopting their former masters' family names. But were they taken voluntarily? Stephen Rigden investigates.

If you ever focus your family research in a particular place – a town, a county, an island – you soon learn to recognise those surnames which are typical of the place. This might be because they either occur frequently or stand out as unusual, or often, in the cases of local names, both.

Good examples are the surnames Camburn and Edenden in Whitstable, Kent, Bolitho in parts of Cornwall, Docwra in Cumberland, Quayle on the Isle of Man and Linklater in the Orkneys. Of course, names move with people. For instance, the surname Docwra is now much more common in Norfolk than in its apparent place of origin in Cumberland.

Bahamian surnames

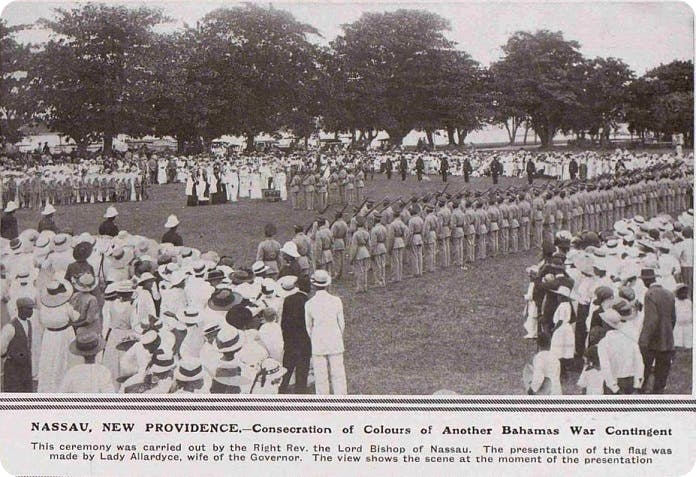

During the First World War, the British West Indies Regiment was a Black regiment led by white officers. All other ranks (NCOs and privates) were black or mixed race. It was raised in 1915 and took volunteers from across the British-administered Caribbean, including British Guiana (now Guyana) and British Honduras (now Belize) as well as the islands.

There were three Bahamas Contingents in 1915 and 1916, which were trained up at army camps in Jamaica before sailing to England, where the British West Indies Regiment had a base in Seaford, Sussex. In addition, there were five Bahamas drafts later in 1916 and 1917.

When reviewing the records of British West Indies Regiment men from the Bahamas, some distinctive names leap out. These include;

- Bethel

- Demeritte

- Fernander

- Hanna

- Ingraham

- Minns

- Minus

- Sweeting

Both Minns and Minus appear to be local names in the Bahamas, rather than one being a result of confusion in the creation of the records. Similarly, Fernander is a bona fide surname – don't wrongly assume that it might be in error for Fernandez.

Rolle

One frequently occurring name is Rolle. In the context of The Bahamas, the surname appears to originate with Denys Rolle, an American Loyalist who re-settled on Exuma, one of the so-called Out Islands of The Bahamas, sometime in the mid-1780s. He was a planter with 20,000 acres of land in East Florida and was at the forefront of slavery in The Bahamas. He brought about 150 African slaves with him to work his new lands on Exuma.

Denys Rolle (1725-1797).

Denys Rolle died in 1797 but his son John, who had been ennobled as Baron Rolle in 1796, inherited his estate. John Rolle soon had the single biggest slave-holding in all The Bahamas. By 1834, he had 357 slaves across four estates under the control of just a single overseer.

John Rolle (1750-1842).

Rolle himself was generally an absentee landlord. He frequently returned to England, preferring to live there. Things hadn’t worked out as he would have hoped on Exuma. The cotton trade had all but collapsed but he wasn’t able to sell or re-deploy his enslaved workforce after the formal abolition of the slave trade in 1808.

Many of the slaves began working their own small plots on plantation land. They grew increasingly independent and impatient with their enslaved status.

Rolle tried to force groups to work as a kind of jobbing gang in Grand Bahama in 1828 and San Salvador (today’s Cat Island) in 1830. This led to a rebellion, led by a slave named Pompey. The slave revolt was suppressed but served its purpose. There was no forced relocation and the workers remained on their plots of land.

The situation was finally resolved with the emancipation of British slaves. From 1834 there was a transitional period when former slaves became “apprentices”, and then in 1838 they were properly freed. On the Rolle estate, they took over the plantation lands, which they then held in common. Apparently, nearly all of Rolle’s former slaves took his family name.

This is the background to the men named Rolle in the British West Indies Regiment, who volunteered (they were not conscripted) to serve in the defence of the motherland. The name was not given to their ancestors by either Denys or John Rolle. The surname was taken at emancipation in 1838, although, it's not clear if the name was taken voluntarily and willingly embraced, or simply given as part of the termination of the system of slavery.

The Sphere, 29 January 1916. View the full article.

Either way, the outcome is the same. The original Rolle family died out. Baron John Rolle died with no children. His former slaves effectively inherited his lands on Exuma, as well as his name.

Other branches of the original Rolle family still survive in the county of Devon, where the family owned land. We wonder if those Rolles realise they are permanently connected by name with the Bahamian descendants of Africans enslaved by their distant relatives.

Armbrister

Although the name may be Germanic in origin, the Bahamian branch of the Armbrister family is usually described as Scottish, even though it first arrived in The Bahamas from the American South. The generations in question are those represented by John Armbrister, his son John Melchior Armbrister (1760-1829), grandson Henry Gibson Armbrister (1794-1855) and great-grandson Henry Hawkins Armbrister (1819-1857).

John Armbrister lived in South Carolina but the family also had interests in East Florida and The Bahamas. Like the Rolles, they were Loyalist when it came to the American Revolutionary War. John moved his family to The Bahamas in around 1761/62 and worked a plantation there using enslaved labour.

University College London’s Legacies of British Slave-ownership database records that Henry Armbrister of San Salvador was compensated by the British state for the loss of his 62 slaves. He received just over £842 in February 1836. The slaves themselves were not compensated.

The ruins of Henry Hawkins Armbrister’s Great House still stand, marked by an official information board, above New Bight on Cat Island. It's preserved as a historic site.

There were three soldiers named Armbrister in the British West Indies Regiment, all from The Bahamas, Privates;

- 2140 Matthew Armbrister

- 2448 Erskin (or Erskine) Armbrister

- 15486 Hansel Armbrister

Matthew (who was from Cat Island) went out with the 1st Bahamas Contingent in September 1915, Erskin with the 2nd Contingent in November 1915, while Hansel was part of the 5th draft in September 1917. It's likely that a male ancestor of each of these three men was enslaved on the Armbrister plantation and took the slaver’s name upon emancipation.

This naming pattern must have been repeated across the West Indies, and presumably in other British colonies where enslaved peoples had laboured for imperial elites. It creates a curious paradox. The planters and merchants may have felt contempt or indifference for the slaves who were compelled to work for them, yet it is the descendants of those same slaves who carry on the family name and have inherited the land. Did the freed men and women who took those names feel empowered by taking on attributes of the formerly powerful?

Related articles recommended for you

Seven surprising finds in the 1911 Census

Discoveries

Who Do You Think You Are? Series 21: here's what you missed

Discoveries

Kamala Harris' family tree tells a tale of migration and education

Discoveries