The names found in the West India Regiment's army records will make you look (and think) twice

3-4 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | November 9, 2020

Oliver Twist. Guy Fawkes. Don Juan. Were these the real names of soldiers in the British Army's West India Regiment? Stephen Rigden investigates.

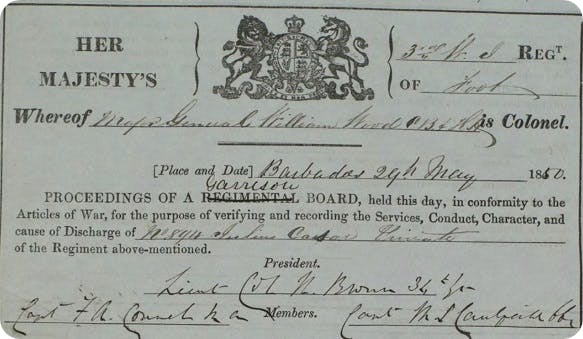

On 24 January 1838, two young men walked into the 1st West India Regiment’s recruiting centre in Freetown, Sierra Leone. They would have been processed in the usual way – undergone a medical and, having been found fit, accepted and enlisted into the ranks of the British Army. They walked out as Private 876 Marcus Brutus and Private 894 Julius Caesar. Private 871 Mark Anthony had already attested a few days earlier, on 16 January 1838.

We think of given names as being the forenames given to a child at birth or baptism. In the context of the British Army and the Empire in the early to mid- 19th century, however, sometimes given names can take on a different meaning.

The three privates named above were aged 20, 22 and 23. They would have had names, African names, appropriate to their backgrounds – two are recorded as being of Igbo (Ebo) heritage and one as Oku (Aku). However, those names were, one has to presume, unfamiliar, perhaps unintelligible or simply too hard to spell, for the British Army, so they were given new names fit for their new army lives.

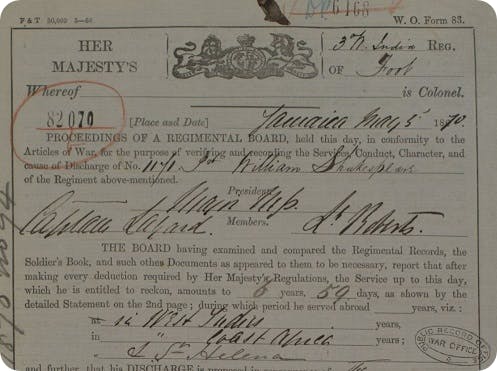

Julius Caesar's service record. View full record.

What do we make of these names and the many others like them? Most of them must have been given to the African recruits by commissioned officers, rather than by the recruiting sergeant, who as a non-commissioned officer is unlikely to have had the kind of background or education that would have prompted these names. The names given to the men speak of a public school and university education. Here are some more, all from 1838/39:

- Beau Brummell

- Guy Fawkes

- Tiberius Gracchus

- Robin Hood

- Victor Hugo

- Edmund Ironside

- Titus Livius

- Don Juan

- Peregrine Pickle

- Walter Scott

- Oliver Twist

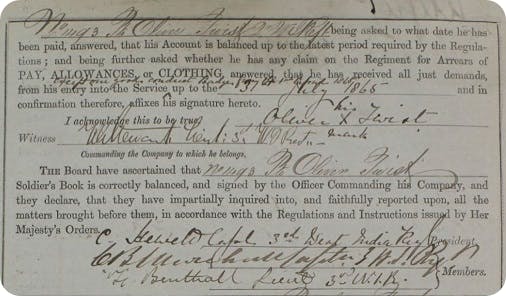

Whoever gave these young Black soldiers their names for their army careers was clearly cultured. As well as the classics, he named the recruits after fictional characters from the best modern literature – Dickens’s Oliver Twist had only just been published in 1838. He selected names from British history and folklore, and he was familiar with fashionable society - Beau Brummell was, at least in his own estimation, the best-dressed man in Regency England.

Oliver Twist's service record. View full record.

Maybe it was a way to relieve some of the tedium of recruitment, 4,000 miles from home on the West Coast of Afric. We can imagine him having a chuckle to himself, or sharing a private joke with a fellow officer as the recruiting sergeant dutifully tried to take down the names. There were some mistakes – we found Private 1154 Bysh Shelly (instead of Bysshe Shelley) and Private 1340 Pearce Egan (instead of the correct Pierce Egan).

The joke isn’t so funny today. Perhaps no harm was meant. Perhaps the grandiose and mock-heroic names bestowed upon young men who didn’t understand the meaning or the joke were meant affectionately. Here are some more names of young African recruits from the 1830s and ‘40s to think about, though:

- Deaf Burke

- George Cocoa

- Dicky Gossip

- Peter Greyhound

- Gunproof

- John Hero

- Titus Hurlyburly

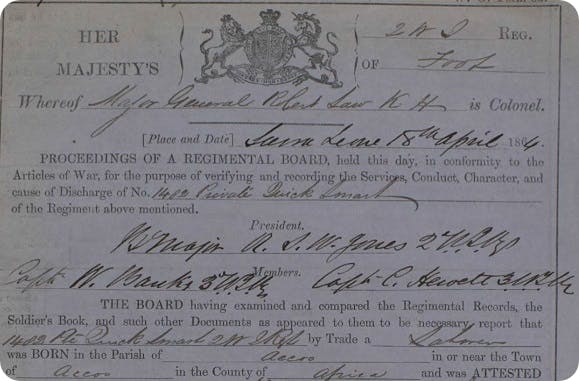

- Quick Smart

- Sampson Strong

The first of these names is clearly offensive. Some of the others may have been descriptive or ironic. Dicky Gossip might have been very chatty or he might have been quiet. Peter Greyhound may have been fast-footed or slow. With a certain type of British humour, you can never be sure – think of Lofty in Dad’s Army, who was a not-so-lofty 4’ 9”.

Quick Smart's service record. View full record.

You wonder what the soldiers of the West India Regiment thought if and when they discovered the meaning of their names. Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith could pass as normal names, and not be recognised as a homage to 18th-century literary figures. But what of the likes of Roderick Dhu, Warren Hastings, Cardinal Mazarine, Sancho Panza, Nathan Rothschild, William Shakespeare, Doctor Syntax and Othello Venice? Did those men ever discover the meaning of the names given to them? And if they did, how did they feel? Some may have been proud to call themselves Benjamin Franklin or Harry Hotspur. Others may have felt humiliated to have been made fools of by the commanding officer or the institution they served. Perhaps they didn’t care, because they held inside themselves their true names and true heritage, and weren't too fussed what their employer called them in official records.

William Shakespeare's service record. View full record.

For some context and comparison in this giving of names, think of London’s Foundling Hospital, which began admitting children from 1741. Those children were baptised and given names (or new names), some of which were taken from classical, historical and cultural sources. The difference is that those names were being given to infants and were part of a framework of care which was as philanthropic as it was paternalistic.

London's Foundling Hospital, 1753.

All the above men in the West India Regiment were discharged to pension, meaning that they often served up to 21 years. That’s how we know of them, because of their surviving army pension papers. Perhaps most of these men didn’t marry or have issue – if they did. It would have been most likely only after discharge, and by then they would probably have been about 40 years of age and, as some of their army service papers say, “worn out”.

But perhaps they leave descendants today, and perhaps some of these names have passed down through the generations in the way that family names do so that somewhere in Britain or West Africa, or the Caribbean, there are men named Julius or Titus unaware of how their heroic names arose.

Related articles recommended for you

Explore new wartime medical records and more

What's New?

These are the nation’s favourite war stories – and the real history behind them

History Hub

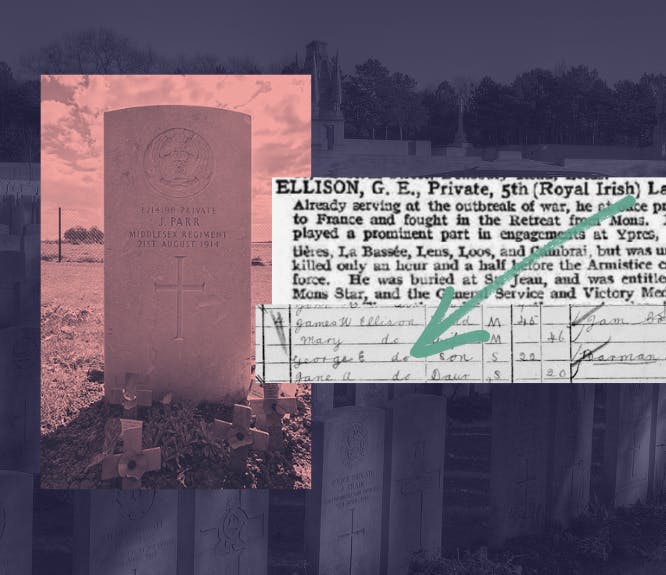

Remember their story: the first and last British soldiers killed in the First World War

History Hub